by Fr Gabriel-Allan Boyd

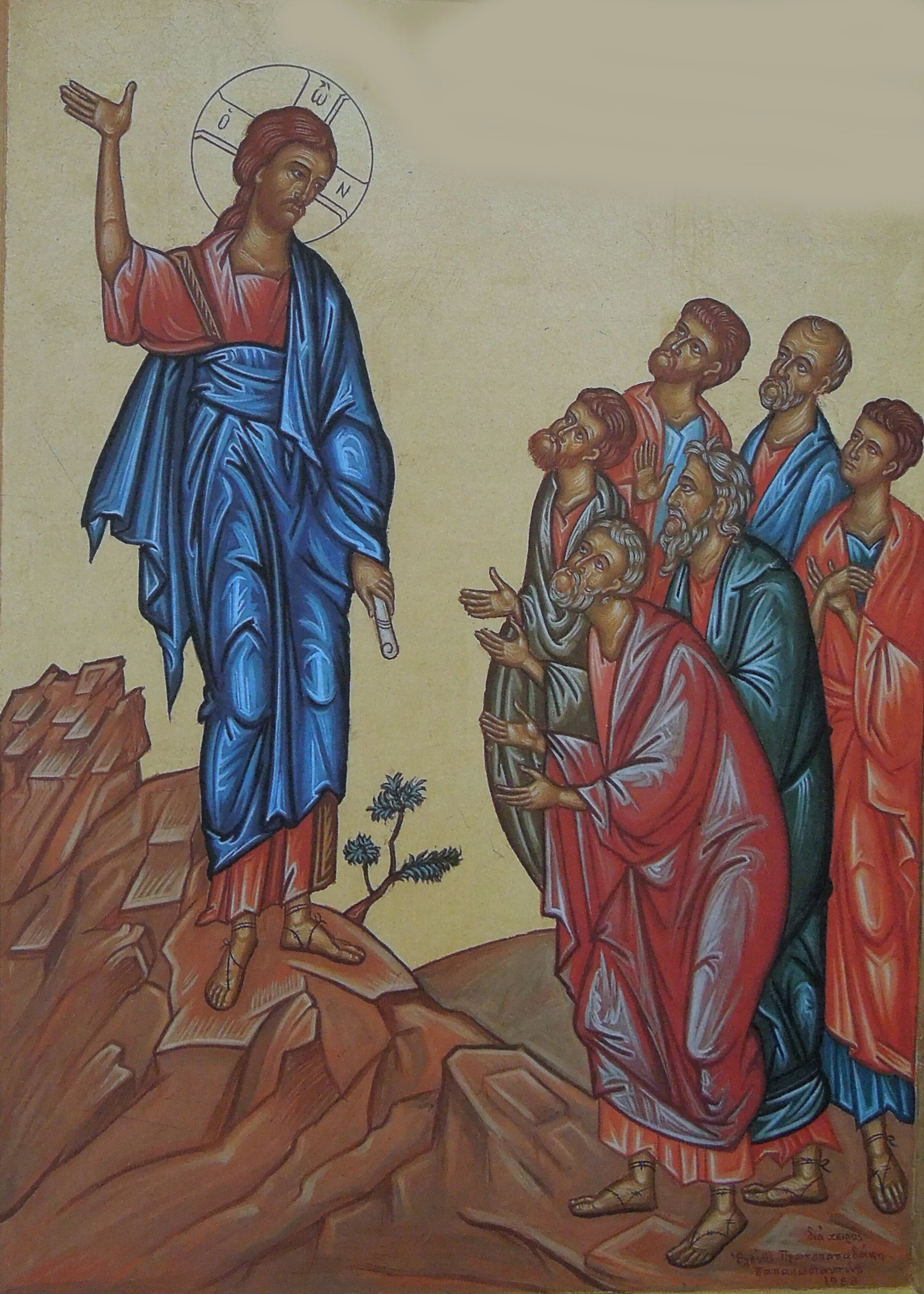

Amidst the celebration of our season of Pentecost, this Sunday marks the feast of the apprentice to the Old Testament Prophet Elijah—the Prophet Elisha. He’s seen kneeling at the bottom right of the icon you see here. Our Orthodox Study Bibles, have Elisha’s story in 4th Kingdoms, chapters 2—9 & 13 (however, if you’re using one of the standard Protestant bibles, you’ll find it instead, referenced in 2nd Kings, chapters 2—9 & 13).

The Prophet Elisha is an Old Testament type of ambassador to the Spirit of Pentecost. In other words, his life and ministry pre-illustrate the coming of the Holy Spirit upon Christ’s disciples, embodying their work in the Book of Acts. In a way, it could be said that Elisha was the first “apostle”—or, “sent one.” He’s filled with God’s Spirit who guides him into courageous, transformative acts offered to a people who had no reason to expect such a powerful expression of God’s loving ministry in their lives.

First, at the beginning of Elisha’s story, we see him being called to discipleship by his mentor, Elijah. The elder prophet throws his mantle over Elisha as a sign of God’s dynamic grace and authority. Elisha then “follows.” Second, when Elijah eventually ascends into heaven, Elisha grievingly prays for a double portion of Elijah’s spirit” (4th Kingdoms 2:9-12). Notice carefully, that he asks for the Spirit of Elijah. It’s as though he’s intensely aware of his need for continuity with Elijah’s ministry (a kind of apostolic succession). Third, after Elijah’s “departure,” Elisha retrieves Elijah’s mantle—his sign of dynamic grace & authority—and uses it to “part the waters” of the Jordan River (4th Kingdoms 2:13-14), like Moses parted the Red Sea in Exodus. It’s as though Elisha comes onto the scene as a new kind of Moses, getting ready to lead God’s people out of their captivity. The Israelites who witness this event recognize that “the spirit of Elijah rests on Elisha.” And so, Elisha has now been set loose to deliver God’s people.

If you notice, Elisha’s story foreshadows the story of Jesus—whose transformative actions leave people awed that God’s dynamic grace is working to disrupt the things that hold God’s people captive: Elisha transforms polluted water into “wholesome water” (4th Kingdoms 2:19-21). He rescues a poor widow and her son from predatory creditors with a miracle of abundance (4:1-7). Elisha bestows a son to a woman and then when that son dies, Elisha raises him from the dead (8-36). He transforms poisonous food into edible food (4:38-41). He feeds 100 people from a small food supply (4:42-44). He heals a Syrian general of leprosy (5:1-27; see Luke 4:27). He recovers an axe head from a swamp by causing iron to float (6:1-7). He transforms a Syrian military threat into a great feast of peacemaking (6:8- 23). He eases a famine in Israel by the work of the wind (πνεῦμα-pnevma) (6:24-7:20). He makes it possible for the previously mentioned widow to receive back her forfeited possessions (8:l-6). He anoints a new Israelite king, disrupting the ones who’d held Israel under their destructive dominance (9:1-16). When we add all of Elisha’s transformative acts together as a whole, the picture, as a foreshadowing of Jesus’ ministry, is stunning.

It’s important to notice that we find Elisha’s story in the culmination of a set of books in the bible called, “Kingdoms.” This is because, a big part of Elisha’s prophetic role involves exposing the rulers of the northern and southern kingdoms in their inability to lead God’s people to a fulfillment of His promises. The beginning of this theme is found in 4th Kingdoms 1:17-19, via the report of Ahaziah’s death (a son of King Ahab). And the dénouement of this theme has a report of Jezebel’s gruesome death (4th Kingdoms 9:30-37). The end of her domination of the people was marked by the report that came back to Elisha, that the dogs had eaten the evil queen’s body, so that the only thing left were “the skull and the feet and the palms of her hands...” (v. 36)—a symbol of her reign’s utter failure and ruin. Over and over again throughout Elisha’s story, the rulers are reduced to irrelevance, showing Elisha as God’s true agent of transformation. As this revolution culminates, we find that only Elisha the prophet has the capability, by God’s grace, to anoint new kings and create new political possibilities, before which incumbent kings are powerless (9:4-10). Without God’s agent in play, feeble office-holders have no power to govern in ways that bring about people’s true flourishing. They can’t heal (5:7); they can’t make peace (6:22); they can’t produce food (6:27). They can’t contribute any dimension of well-being to common life, nor health-care, nor foreign-policy, nor subsistence. Without God’s agent in play, they can’t do anything that rulers are supposed to do. Elisha’s role is to deconstruct and expose their emptiness of the Godly virtues that bring about the world’s flourishing.

This is Pentecost in the face of the dark powers of the world, of whom Saint Paul speaks. “For we are not fighting against flesh-and-blood enemies, but against evil rulers and authorities of the unseen world, against mighty powers in this dark world, and against evil spirits in high places” (Ephesians 6:12). The Spirit of Pentecost in you doesn’t cower in fear, dreading the power of the evil rulers and authorities of the unseen world, but rather, disregards them as irrelevant to the impact of God. The Spirit of Pentecost in you isn’t intimidated by the mighty powers in this dark world, but rather, refuses to swear any fealty to their empty forms. The Spirit of Pentecost in you has other courageously self-sacrificial, loving wonders to enact that intimately connect our common-life to True Life—offering wonders over which the evil spirits in high places have no power.

Here are three things about Elisha’s story that should inspire us now during this season of Pentecost. First, remember what happened after Elisha’s death. By accident a dead man (a symbol of the result of the powers of this dark world) was thrown into Elisha’s grave. “As soon as that dead man touched the bones of Elisha, he came to life and stood on his feet” (4th Kingdoms 13:21). Orthodox Christians should know that we’re recruited for transmitting life to the dead. Second, since Pentecost follows Easter and the gift of new life, then Pentecost is about seizing the public out of the deadly works of the “rulers and authorities of the unseen world.” Third, after the pattern of both, Elisha and the Book of Acts, Pentecost is a special time to consider how the people of God position themselves in a society where anxiety and repulsion of personal accountability to God rule the day. It should become clear to us during this season, that when our motivation is about keeping Christianity comfortable for us and comfortable for everybody in the world around us, then we’ll never experience or transmit to those around us the power to transcend and transform and our common life. We’ll continue to be confounded by what we face. What a time we are in right now for embracing the Spirit, the wind (πνεῦμα-pnevma) that blows beyond our preconceived notions of a comfortable Christian life. Pentecost isn’t for the magical thinking of hoping to experience God’s grace in various “miraculous” phenomena. Rather, it’s for slow, steady obedience to what we can’t grasp. This work enacted by the Spirit concerns the communion of saints, a call to the repentance of and forgiveness of sins which bring death upon our lives, heroic (self-sacrificial) acts of love on behalf of others, and the offering of true-life to that which is dead. All of that is well beyond comfortable Christianity!

Our Church is, as we say in the creed, “one, holy, catholic, and apostolic” We are apostolic—sent with a message. And so, as Orthodox Christians, this is the vocation to which God calls each of us, as ones who carry God’s life-giving (πνεῦμα-pnevma) Spirit. As Elisha’s life demonstrates, Pentecost is the invitation to become “new creatures” (2 Corinthians 5:17) in this world—ones who boldly participate in the work of the Spirit—refusing to be hindered by the mighty powers in this dark world. And so, we discover that the process of Pentecost—of embracing and yielding to God’s Spirit—is a demanding one. Our core work in Pentecost is to embrace God’s Spirit, asking for “a hard thing,” as Elisha did, with a sense of both awe and desperation, for a double-portion of the Spirit, to carry on the work of the apostles—ones who are sent into the world to transform the distortions of the powers that be.